| Published on Dec. 4, 2018 | In the Columbia Missourian |

| Download file | View online |

The rate of suicides across the globe has steadily decreased — except in the United States.

Suicide increased significantly in the U.S. between 1999 and 2017, according to a newly published Centers for Disease Control report. Missouri’s figures mirror the national trend.

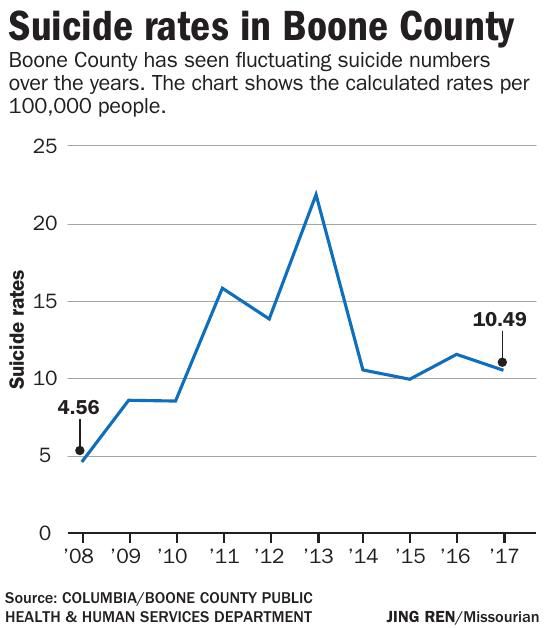

In 2017, the rate for Boone County was 10.49 suicides per 100,000 residents, compared to 2008’s rate of 4.56, according to Jason Wilcox, a senior planner at the Columbia/Boone County Public Health and Human Services Department. The county’s rate has increased since 2008 but dipped since 2013.

Missouri has an above-average suicide rate. In 2017, while the national rate was 14 per 100,000, Missouri’s was 18.49, according to state data from the Missouri Institute of Mental Health. Download PDF

The state figures are even more alarming when looking at the population ages 10 to 24.

One in eight Missouri middle schoolers and one in six high schoolers seriously considered suicide in 2017, according to a student survey cited in the institute’s report. That same survey showed that 6 percent of middle and high schoolers had attempted suicide in 2017.

One in five college students have seriously considered suicide in the past year, according to a separate 2018 survey.

The per capita suicide rate increased 33 percent nationwidesince 1999, according to the CDC report. The government’s goal for the nation’s suicide rate is to reach 10.2 per 100,000 people by 2020 — below the 1999 rate — but increases suggest the U.S. is not on track to hit that goal.

While males still die by suicide at significantly higher rates than females — there was a 26 percent increase in that group since 1999 — the increase in the suicide rate for females was 53 percent higher than in 1999.

Suicide is the 10th-leading cause of death in the United States. Since 2016, it has been the second-leading cause for people between ages 10 and 34.

Providers’ responses

Suicide is known to occur in higher rates in rural counties than in major metro areas, but the gap is growing larger. The rural county rate, 1.4 times that of urban counties in 1999, has increased to 1.8 times that of urban counties today, according to the CDC.

Bart Andrews, vice president of telehealth and home/community services for Behavioral Health Response, said suicide in Missouri reflects that rural-urban divide.

Behavioral Health Response in St. Louis operates a crisis line for much of eastern Missouri and answers calls for multiple state crisis hotlines and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

Andrews said the organization is handling the increased call volume, but it gets harder and harder each year. He said it can be difficult to connect callers to ongoing services.Missouri’s specialized outpatient mental health services can be hard to access, especially in psychiatry, Andrews said.

“The need for services outweighs our capacity to provide those needed services in a timely fashion,” he said.

Behavioral Health Response received a grant from the Missouri Foundation for Health for follow-up care that resulted in reduced suicidal thought and emotional pain, and the group was able to get most of those callers connected with ongoing care. Follow-up calls, he said, are needed across the health care system, as well as better insurance coverage and access for people in need.

John Lauriello, medical director at MU’s Missouri Psychiatric Center, wrote via email that it is important for mental health care providers to realize “not all suicides are due to depression. People can (commit) suicide because they have poor impulse control, are angry, are demoralized or feel isolated. Sometimes that means they are also depressed but not always.”

Substance abuse is also playing a role in suicide rates, he wrote.

“Substance use of all kinds increases depression and clouds judgment and increases the risk of suicide,” Lauriello said. Mental health care providers need to be aware of that, but also of other risk factors including “recent loss, or a major financial or educational setback.”

“Other untreated or inadequately treated disorders like PTSD, bipolar or schizophrenia can increase the risk,” he said.

Community mental health centers cover the entire state and suicide helplines are available, but receiving care isn’t always easy, Lauriello said.

“Access to care can be difficult,” he said, “but make sure that when you reach out for yourself or someone else you tell them if the person is suicidal.”

Even when care is available, many can’t afford it. Medicaid expansion, which Missouri declined, would have made it a lot easier to provide affordable care for Missourians with mental health needs, said Andrews, of Behavioral Health Response.

“(It) would have increased our ability to connect people to services substantially,” Andrews said. “There’s just not enough money to help people who are uninsured.”

The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, a national organization coordinating prevention efforts, wrote in a statement that funding for suicide prevention is disproportionately small compared to “other major public health issues.”

The alliance encouraged increased private and public investment, public education and resources to help combat the problem, as well as better services and treatment by health care providers for people considering suicide.

The alliance also recommends reducing access to the means of committing suicide, including lethal doses of medications and firearms. More than half of all people who took their lives in 2016 used a firearm, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.